The atmosphere contains 15.5 x 10^12 cubic metres of water or 0.001% of the Earth's total water reservoir volume of 1.46 x 10^18 cubic metres. Water reservoirs include the atmosphere, ice and snow, biomass, surface water, underground water, and the oceans. Even if all 7.9 x 10^9 people on Earth used water from water vapour processors at the rate of 50 litres per day, they would consume temporarily only 0.0025% of the available atmospheric water. In 2100, when population is expected to be 10.9 x 10^9, this worst case impact would rise slightly to 0.0035%.

The most recent water cycle information I could find was from the AGU (1995). The per capita water consumption value of 50 L/day was suggested by Gleick (1998) for domestic water requirements (drinking, kitchen, laundry, and bath). Today's population estimate was from Worldometers. The year 2100 population estimate was from Wikipedia:Projections of population growth.

Water vapour, the gas phase of water, diffuses along water vapour pressure gradients to zones of lower water vapour pressure. If a lot of water vapour was condensed into liquid water in a specific region such as a city, for example, water vapour from outside the region would flow into the region. No net loss of atmospheric water vapour would be observed in the city.

Water consumed for domestic water requirements does not exit from the water cycle. Within several days the liquid water that is used or with-held temporarily from the water cycle would be returned to the environment to evaporate into atmospheric water vapour.

Using a new technology such as atmospheric water vapour processing in drinking-water-from-air machines may have other impacts on Nature. These include

- possibility for more people to live in a region, increasing the population density;

- increased sewage and other waste (including material waste from machines which have reached the end of their operational life);

- increased energy use (to operate the machines); and

- increased material use (to build the machines).

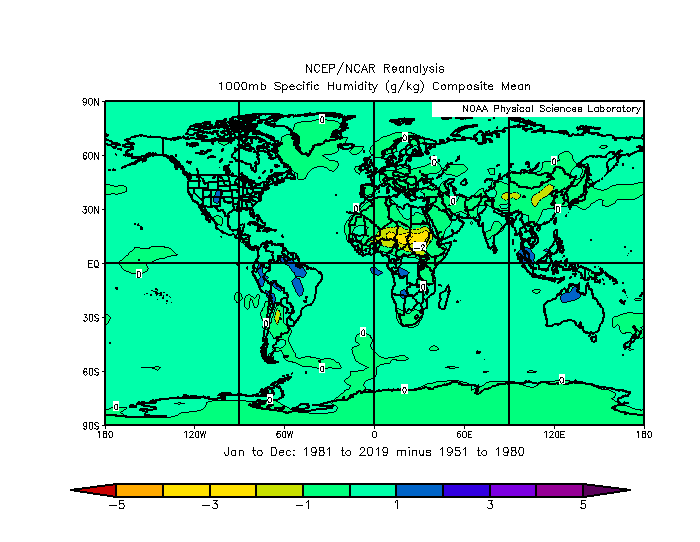

A recent analysis by me about the direct environmental impact of widespread use of dehumidifiers and air-conditioners dripping condensate from millions of machines since about 1950 showed that the specific humidity field at Earth's surface has been remarkably stable over the past 70 years (see the figure above and the associated earlier blog post). In fact, Wikipedia: Air Conditioning stated, "According to the IEA [International Energy Agency], as of 2018, 1.6 billion air conditioning units were installed,...." The same Wikipedia article said, "Innovations in the latter half of the 20th century allowed for much more ubiquitous air conditioner use. In 1945, Robert Sherman of Lynn, Massachusetts invented a portable, in-window air conditioner that cooled, heated, humidified, dehumidified, and filtered the air."

In summary, scenarios involving the entire human population using processors of atmospheric water vapour are unlikely, so it is also unlikely that water-from-air technologies will cause a drier atmosphere in the context of the Earth’s water cycle and natural processes of water transport and distribution.

References:

AGU (1995). Water vapor in the climate system. Special Report. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union.

Gleick, P. H. (1998). The World's Water 1998-1999: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Wahlgren, R. V. (2018). Water-from-Air Quick Guide. Second edition (reprinted July 2018 with minor corrections). North Vancouver, BC, Canada: Atmoswater Research.